For a podcast version of this newsletter, you can listen on Spotify or in your browser.

—————————————

At the end of the year, I’ve been returning to a much beloved book: Dorian Lynskey’s 33 Revolutions Per Minute. Lynskey’s book is a series of 33 essays on different pop music scenes and genres throughout the 20th century, and their relationship to politics and activism.

‘The border between artist and activist is a treacherous one: you cross it at your peril. Bob Dylan caught a glimpse of what was on the other side and turned back. Billy Bragg and Bono, in their different ways, pressed on.’

It’s a great set of reflections on the ways pop music has tried (and failed) to engage with politics, as well as a fantastic set of historical anecdotes for music nerds. It also, inevitably, makes me think about the relationship between art and politics in my own practice.

——

I never set out to be a political artist. My key obsession as a young writer was worldbuilding, creating conceptual sci-fi and fantasy universes and trying to put them on stage. Later, I was drawn to writing about science, and about the research efforts to understand the planet as it transforms around us. But that wasn’t because I had a political ideology that I wanted to express - the impulse in me was always to understand this moment.

But because climate science has been politicised, making art about climate is also political. Without meaning to, my work began to be read through the lens of politics - what was I arguing for, in this play? What change did I want to see in society? Whose side was I on?

It would be disingenuous to pretend I was completely naive about all this. Writing Kill Climate Deniers was a deliberate choice to run full tilt at the culture war, to roll up my sleeves and get involved.

But subsequent works of mine have been far less political, far less direct in their engagement with climate politics. In solo shows like You’re Safe Til 2024 or Deep History, I’m much more interested in the experience of living through this moment, how climate change affects us on a psychological and emotional level. If those works are political, it’s mostly in the sense of how political identities frame (and distort) our perspective of our wider ecological context. But that hasn’t stopped them being read through the lens of politics.

This is the challenge of making art about the climate, as distinct from other subjects. The way that we talk about climate change tends to be as a political issue, a clash between left wing and right wing. For journalists writing a quick story about a work of climate art, it’s much easier to talk about climate change as a battle between two sides than it is to talk about a huge abstract unravelling of all the global systems that underpin our society and biosphere.

So if you create a work of art about climate change and earth science, you can be sure that interviewers will ask you questions like: ‘How can we defeat right wing politicians?’ and ‘How can we make more people active in the fight against climate change?’

I don’t know! I never have!

Sometimes I feel that the media deliberately asks artists these impossible questions to reveal how ignorant we are. Irwin Schmidt, the keyboardist in the iconic German band Can, remarked in 1971 that, ‘TV is not at all interested in the political opinions of people who also want socialism and a more human society, [and] can spell it out. I am insecure, I know much too little... so television, being gloriously critical of society, can take me as an example. So that it can preach: 'look, they do not know what they want!' [A little] bit of the revolution we want is included in the music, but you can destroy this when you manipulate the musicians in such a way that they are forced to interpret their music with words…’

Of course there’s nothing so sinister at play. Journalists would like nothing better than for artists to be able to tell them in a few glib lines how to rearrange our society for the better. We can’t. No-one can.

Lynskey puts it like this: ‘What right does a musician have to discuss politics? What place is there for serious political issues in entertainment? And the answer is the same as ever: there comes a point where we have to accept that a musician does not have the same responsibilities as a politician, and that music can contain, and derive energy from, ambiguities that an interview cannot.’

(For musician, read ‘artist of any kind’.)

So what are the capacities of the artist in terms of creating political work?

1. To take multiple sides

One thing that theatre has a particular ability to do is to hold multiple viewpoints on a single issue. A theatre show can argue against itself from different angles, using different characters and perspectives. This is great for a person like me who is never sure of where they stand on a particular topic, especially one as loaded and complex as climate.

Of course, taking multiple sides is no excuse for making timid art. My favourite theatre shows operate with a kind of aggressive doubt - making strong statements and questioning them equally strongly. I think the artist should commit to a stance or a viewpoint on a subject - and then once they’ve committed, they should critique that stance as hard as possible. I think an artist should be making the case against their own self as strongly as possible, trying to find the gaps and holes in their thinking. Make mistakes, then own up to them publicly and see what lessons can be learned.

2. To create experiences

The best political art speaks to the issues not (just) through its content, but through its form. Theatre (and all art) can capture the contours of a political issue experientially as well as intellectually, through the aesthetic contours of the work. Writing about political bands such as Public Enemy and the Clash, Lynskey says, ‘They understood that you had to fight spectacle with spectacle, amplifying all the cultural white noise, then projecting it back in a scree of sounds, slogans, images and high-wire rhetoric.’

Lynskey captures what this looks like in his description of Public Enemy’s second album, It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back:

‘Where other producers went with the flow of their purloined grooves, [Public Enemy’s producer] Shocklee talked of creating a ‘hailstorm’ of samples, in heavy and constant motion. The music conducted its own dialogue with black history, layering chunks of James Brown and Sly Stone between fragments of speeches by Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam’s self-proclaimed ‘truth terrorist’ Khalid Abdul Muhammad, punctuated with air-raid sirens, jagged bursts of turntable scratching, cries and grunts. Classic protest songs were embedded in the mix: a line from ‘Living for the City’ here, a refrain from ‘Get Up, Stand Up’ there. These elements didn’t merge so much as collide. In keeping with Chuck’s alarm-call analogy, Public Enemy used dissonance and rupture to blast the listener awake and take them, to quote one song title, ‘to the edge of panic’.’

When it comes to work that grapples with the climate, there are no emotions that are off-limits. Climate change is the background of all the other crises in our world, it suffuses everything we do, and so a work of climate art can be rich with joy, grief, anger, euphoria or desire, or all of them at once. Everything is on the table.

3. To convene gatherings

Art, particularly performing arts, can be a space for people to come together. A concert or a theatre show is a space for people to convene, to meet and mingle, and to share an experience. A shared experience of a performance about climate change has the power to remind people that they’re not alone in feeling overwhelmed by this issue and unsure of how to deal with it.

Given the strange and spiky nature of much of my writing, I never thought my work could possess this kind of healing power. I often feel like I’m poking and prodding the audience, making people laugh with a dissonant edge. Then, during my season of Deep History at the Public Theater in New York this November, I was programmed to perform two shows the day after the US election.

I was certain that the shows would be a disaster - if anyone even showed up at all. They turned out to be the two best shows of the season. People laughed, cried, cheered. I guess in the aftermath of a hard national moment, people needed a space to come together to process big feelings collectively. On that day, my show was it.

But why did my show, about the experience of the 2019-20 bushfire season in Australia, resonate so strongly with Americans in the context of a national election? Talking with audience after the show, what struck me was that the connections they made between the two events weren’t obvious or direct. It was the moments where my emotional disorientation during the fires happened to rhyme with the feeling of navigating the current US political landscape, that was what connected.

I think if the show had been about the US election, it would have been, at that moment, too much. Too direct, too claustrophobic, no room to breathe. The fact that the show was about something else allowed audiences to escape their own context for a moment, and then to rediscover their context from a different angle, to reframe it through a different lens. Art, here, has the power to help us escape our current situation, and in doing so allow us to reimgine it on different terms.

——

There are many ways that artists can effectively engage with politics in their work. The list above is just the beginning, there are so many more examples. But whatever you do - and this is a lesson I’ve learned the hard way - your work cannot get caught at the level of politics. You can make good political art, but your art can’t only be political, or else it may as well just be a tract or a sermon.

Good art is always aiming at something higher, something deeper. It will take in politics along the way, but it has to reach for a beauty and a meaning that can’t be contained in the language of politics. Politics is the surface of the ocean, the wind and the waves and the snow dissolving when it hits the water. Below the ocean’s surface are the deeper layers of emotion and lyricism, the layers that resist categorisation through a political framework. Spiritual currents, romantic, erotic, disturbing, joyful, playful, awe-inspiring, painful and mournful currents.

As an artist, you have to dive below the surface, below the crashing and foaming and white water, below the currents and the tides, all the way down, to where the water is still and the light runs out. This is where the real art happens.

When you work from the depths, you can’t always predict how the politics of the work you create will look. Sometimes critics and audiences find a different political lesson in the work than the one you intended. But this is part of the pleasure of making art in this world - it’s unpredictable, elusive, surprising. We each inscribe a shape on the ocean’s surface through our motions underwater. But try as we might, no-one can write clearly on the wave.

-------

NEWS AND PROJECTS

Deep History at the Public Theater

As I mentioned above, I spent five weeks over October-November in NYC performing Deep History at the Public Theater. It was an absolute joy - getting to share the show with a bunch of fascinating, receptive audiences, and engaging with a whole new theatre community. My first show at the Public, but very much not my last.

TED talk

Since my TED talk went live in September, it’s racked up about 850,000 views, which is a delight. I’ve had lots of lovely conversations with people who’ve reached out since watching it - it feels like this really resonated with people.

One of the most lovely conversations I had around the video was on TED’s How To Be A Better Human podcast. Host Chris Duffy was one of the most thoughtful and switched-on interviewers I’ve ever encountered, and it turned out to be a really rich and fascinating conversation. Really pleased with this one.

Systems gaming in Singapore

This November, I was delighted to get to run a two-day workshop on game design and systems thinking for public servants in Singapore as part of the CAST (Applied Simulation and Training) program at the Singapore Civil Service College. This is the second year I’ve collaborated with CAST on this workshop, and it’s becoming one of the highlights of my year - they’re a fantastic group, doing incredible work using games to navigate complex challenges. It was also a pleasure getting to run a workshop again - if anyone is interested in anything for 2025, get at me.

Secret project in Manila

For the last couple of years, I’ve been working with lifetime collaborators Adrienne Vergara, Sig Pecho, Brandon Relucio and Sam Burns-Warr on a big new performance project in Manila. We’ll be announcing the show in late January and going live in May 2025, which is very exciting. In the meantime, please let me share this photo of me from a film shoot in Manila in November. The emotion I was going for here is ‘pensive’.

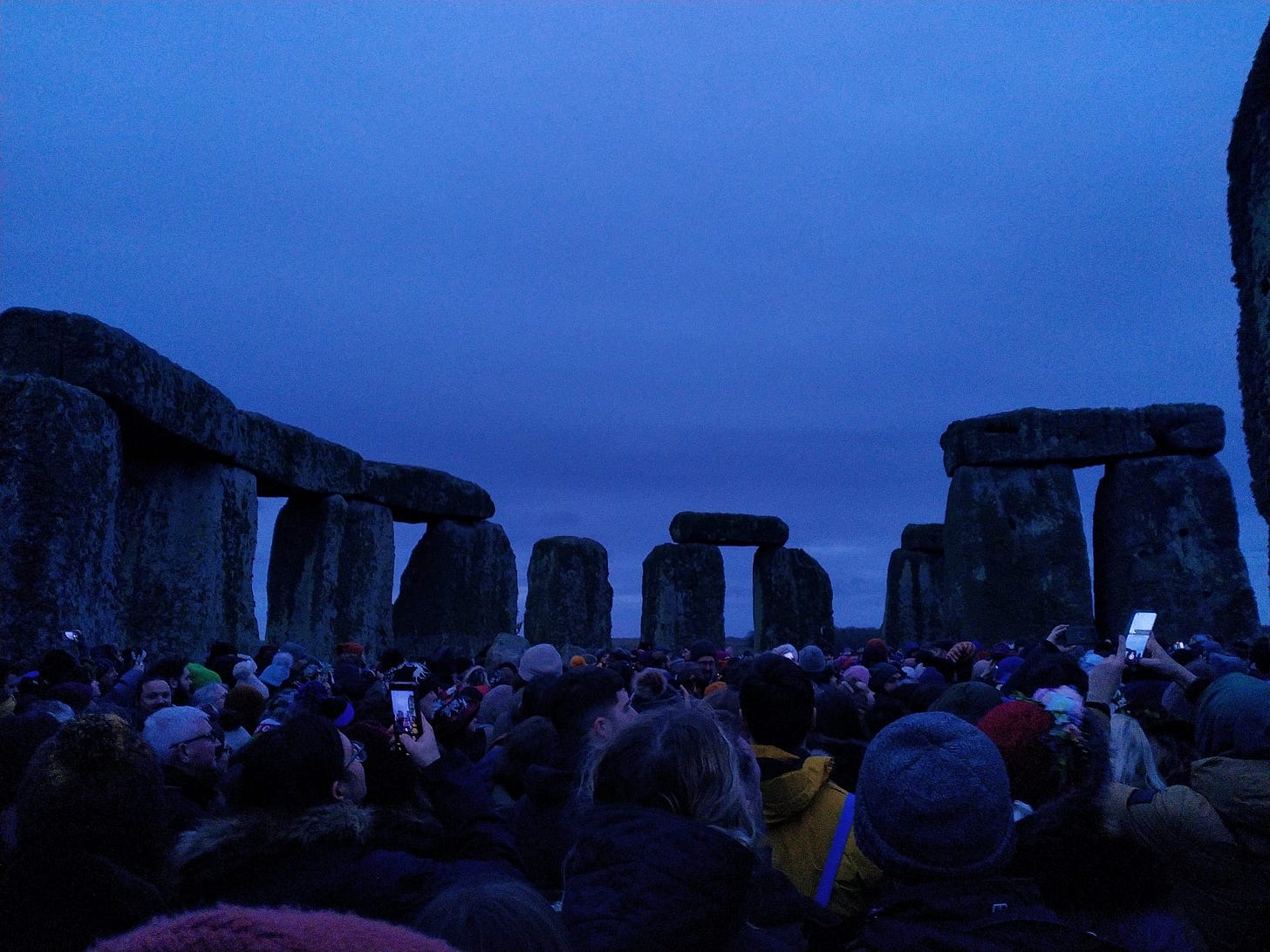

Stonehenge

Rebecca and I went to Stonehenge for the winter solstice - truly one of the strangest and most British things I’ve ever done in my life. It was somewhere between ridiculous, chaotic and (at one moment) actually deeply profound. Gonna be thinking about this for a while.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Can - Halleluwah

I quoted Irwin Schmidt from Can in the newsletter above, and so now I’m obliged to include one of the best Can songs of all time, which therefore is one of the best songs of all time. This tumbling drum fill, forever.

MIA - Galang

And speaking of political art and ‘aggressive doubt’, I feel like I have to include this all-timer from an artist who managed for a brief* moment to inhabit all the contradictions and complexities of politically-infused art and to create something extraordinary with it.

*all too briefly

Adrian Hon - You’ve Been Played

Hon is a world-famous game designer, but I mostly love him as a writer and game critic. His newsletter is a must-read for anyone interested in game design, and his book on game design practice is just as good as I was hoping. He’s a sharp critic on the worst excesses of ‘gamification’ (hence the title), but it’s the chapter analysing conspiracy theories like Qanon as examples of ARGs (alternate reality games) that makes this worth the purchase price. Loved it.

---

As ever, you can get more background on my practice in my New Rules for Modelling series, or you can check out my website. And if you have any questions or offers that might make my life more interesting, feel free to get in touch.

Peace!